England: history of the pipe and tabor

the 16th century theatre jig

based on an article by Lucie Skeaping

Sexually explicit jigs were a major part of the attraction of the Elizabethan, Jacobean and Restoration stage.

The crowds who flocked to the London playhouses in the late-16th and early-17th centuries could

expect to be amused, amazed and moved, in many cases, if they stayed on after the play had ended.

Then they would be treated to a rude, lewd farce, commonly known as a ‘jig'.

The celebrated jig-maker and clown Richard Tarlton (1530?-1588), often made his stage entrance

playing the pipe and tabor.

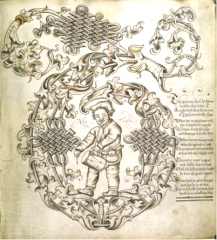

end 16th century alphabet book f. 19 end 16th century alphabet book f. 19 |

'"The picture here set down, John Scottowe (d. 1607), |

The same stock characters turn up again and again: cuckolded husbands, adulterous wives, milkmaids,

whores, wide-boys, muggers and thieves, along with lecherous soldiers, fishwives and a variety of street

traders who get drawn into the plot.

There are few specific references to dancing in jigs but, along with

various movements, acrobatics and rhythmic gestures, dance was undoubtedly a major feature.

"The players mean to put their legs to it as well as their tongues," wrote the satirist and clergyman

Donald Lupton in 1632.

Of the 12 surviving English jig texts roughly half contain specific tune titles alongside

the text, that is, the names of popular ballads or dance tunes of the day. Lines ending in ‘fa la la' naturally

indicate singing and invariably where a new tune title is prescribed it corresponds with a new metre or

rhyme-pattern in the text.

Not everyone approved of the post-play jig. The playwright Thomas Dekker wrote in 1613:

"I have often seen, after the finishing of some worthy tragedy or catastrophe in the open theatres that the scene after the Epilogue hath been more blacke – about a nasty bawdy jigge – than the most horrid scene in the play was."

To the literary world they were an object of disapproval. Ben Jonson (1572-1637) loathed the ‘concupiscence

of jigs', believing they prevented audiences from appreciating plays. The satirical poet Everard Guilpin

(born c. 1572) dismissed the ‘whores, bedles, bawds and sergeants' who ‘filthily chant Kemps Jigge', noting how

, on leaving the playhouse fired up with lust, ‘many a cold grey-beard citizen' would sneak into

‘some odde noted house of sin'.

By October 1612 jig performances were attracting so many criminals and disorderly crowds – who often

visited the theatre for the jig alone with no intention of seeing the main play – that the Middlesex Magistrates,

north of the Thames, saw fit to issue:

"An Order for supressinge of jigges att the ende of playes … by reason of certayne lewed Jigges songs and daunces used and accustomed at the playhouse called the Fortune in Goulding-lane, divers cutt-purses and other lewde and ill disposed persons in great multitudes doe resort thither at th'end of everye playe, many tymes causinge tumults and outrages […] it is hereupon expresselye commaunded that all Actors of every playhouse […] utterlye abolishe all Jigges Rymes and Daunces after their playes".

top of page